Taxation

My position: Collect appropriate taxes

The proposals below are intended to slow the growth of the national debt so that with the addition of spending reforms, we can grow the economy around it and reduce the debt to a manageable level over time.

Raise the corporate tax rate. The Congressional Budget Office recently analyzed impacts of raising the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 22 and to 28 percent. I favor increasing it to the 28 percent, with further analysis of impacts of 30 and 35 percent.

Raise the top two individual income tax rates, from 35 percent to 36 percent for incomes over $250,000 (single filers) and $500,000 (married filing jointly) and from 37 percent to 40 percent for the top bracket (above $626,000 for single filers and $751,000 married filing jointly). (The income levels I use are the approximate levels in 2025; I intend for the tax policy to apply to the top two levels as they are currently determined.)

Restore estate and gift taxes to the levels that would have applied upon expiration of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act had the One Big Beautiful Bill Act not replaced them.

Reverse tax cuts for special interest groups (tax on tips, tax on social security benefits). Assess tax on income level, not source.

Increase tax on capital gains for higher earning households.

Fully staff the IRS and set them on finding tax evasion.

Restore and enforce the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax.

Hunt down and close tax loopholes used by high income people and corporations to avoid taxes.

I oppose wealth taxes (other than estate and gift taxes) and taxes on unrealized gains.

Tariffs are taxes too, and I oppose tariffs except when carefully focused toward realizable goals.

Some Background

Why I broke from the Republican orthodoxy on taxation.

Growing up in a Republican household and through my career in the military, I accepted the Republican orthodoxy that lowering taxes stimulates economic growth, eventually benefitting everyone. It makes sense to me that high taxes, especially on the most productive people and corporations, would have a chilling effect on growth. Individual income tax rates have been as high as 94 percent, leaving a worker 6 cents for every dollar earned after that point. Who would bother to work anymore once they reached that level? I personally enjoyed each time lawmakers lowered my tax rate and I got a larger refund. The economic growth it drove made a nice story to tell myself, too: my larger refund helps the economy grow. Cut taxes, the economy grows, and we all get more. Everyone wins.

The problem is that the evidence does not support the theory. Historically, changes in individual tax rates have had very small effects on economic growth. The U.S. has collected federal income taxes for more than a century, with the top rate reaching that high of 94 percent at the end of World War II, and a low of 28 percent under President Reagan. Research by the Congressional Research Service and numerous governmental and non-governmental organizations find that the effects of tax rate cuts for individuals on economic growth have been small, sometimes barely measurable. The same holds the other way: raising individual income tax rates, particularly on high earners, has had a very small negative impact on GDP, often close to zero. Corporate tax rate changes have also shown very small effects on GDP, though modest effects on business investment and capital stock.

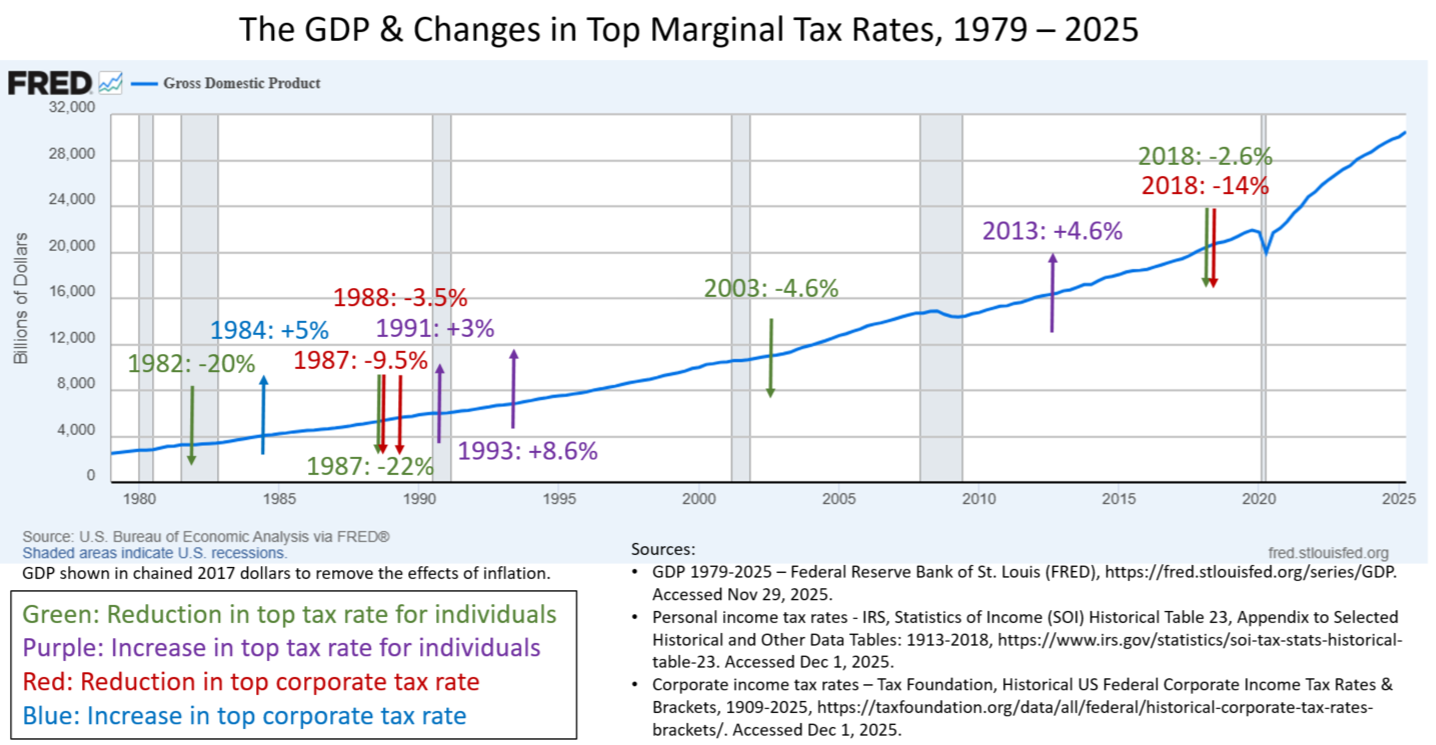

An article by Corey Husak brings a lot of this research together in a useful way, but I like to look at it in light of the chart below. Lay the many tax cuts and increases starting with the Reagan era over the GDP, and there’s no noticeable impact of those changes. Any effects they may have had were overwhelmed by other macroeconomic forces of the day. The Republican orthodoxy – tax cuts stimulate the economy; tax increases slow economic growth – is unsupported.

Tax cuts do have impacts, though: they reduce revenue and add trillions to the national debt.

Overwhelmingly, our government analytical centers warn that our debt is on an unsustainable long term trajectory, and the loss of revenue from foregone taxes contribute trillions of dollars to its growth over a decade. If we want to get our debt under control, we need to keep our spending down and collect enough revenue to cover the primary deficit. That means collect taxes. My position, to increase corporate taxes and taxes on households with the highest income levels, is not intended to punish the rich or pursue economic justice. It is intended to address our runaway debt through an additional, but not excessive, load on those who can best bear it.

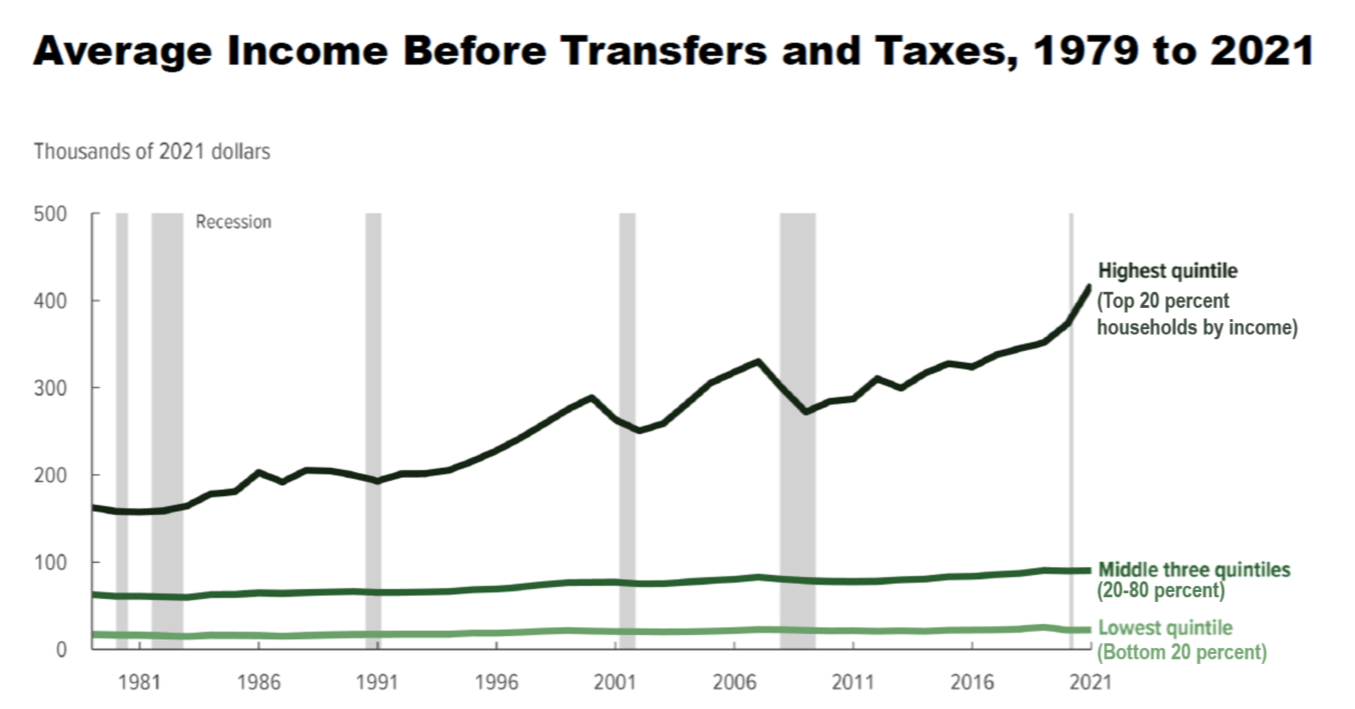

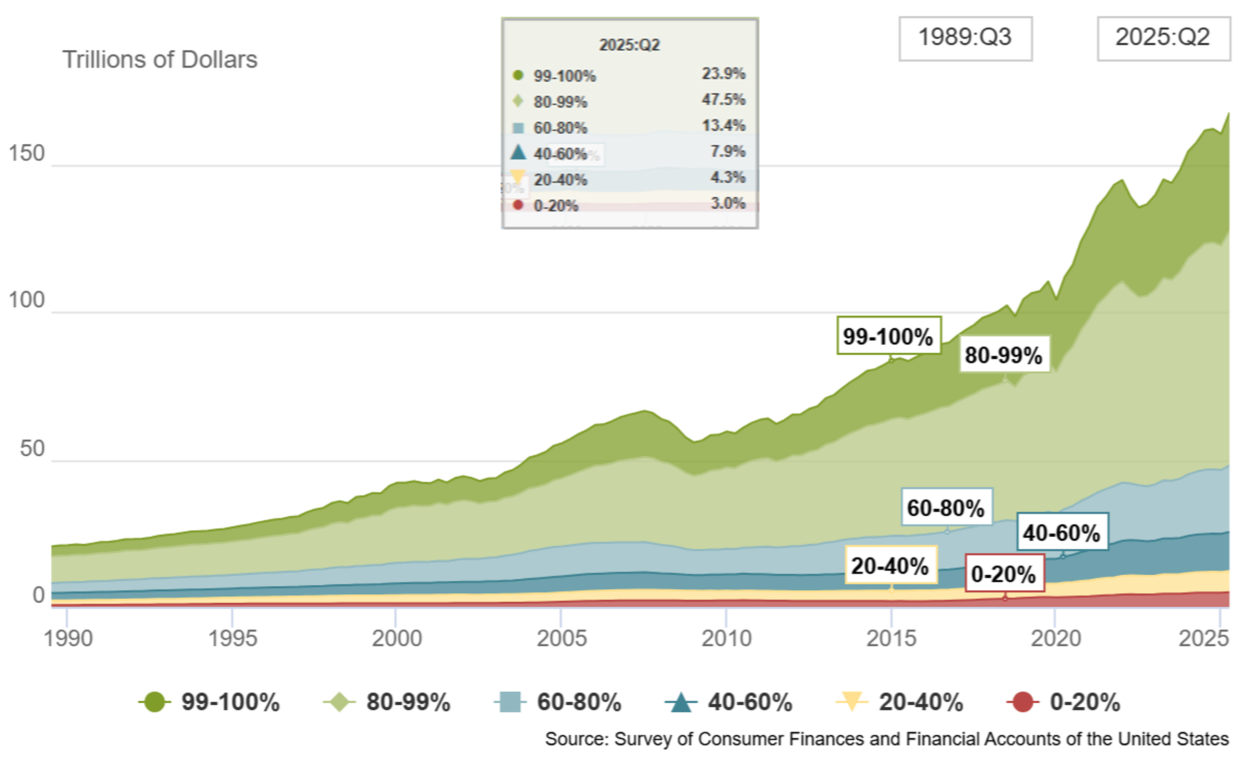

The last four decades have seen the growth of incomes and wealth as well as GDP, especially in the 20 percent of households with the highest income levels. According to data from the Federal Reserve, by mid-2025, the top 20 percent of households by income held a little over 70 percent of the individual wealth of the nation. (For perspective, the 80th percentile starts at about $150,000 annual household income, and the 90th percentile starts at about $250,000 annual household income according to the 2022 Federal Reserve Board Survey of Consumer Finances.) These changes in income and wealth over the past few decades are shown in the two graphics that follow.

Source: Congressional Budget Office “Trends in the Distribution of Household Income From 1979 to 2021,” https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60342Wealth by Income Percentile

Source: Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/dataviz/dfa/distribute/chart/#quarter:142;series:Net%20worth;demographic:income;population:1,3,5,7,9,11;units:levels;range:1989.3,2025.2Cutting taxes for the highest earners, as was done in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the recent One Big Beautiful Bill Act, adds to our debt without stimulating the economy. Take away the assumption that tax cuts for high earners pay off with growth of the economy as a whole – an assumption unsupported by a century of evidence – and we are left with a national debt growing even faster to reach a level we’ve never seen before.